Thicker Than Blood - Crouch Blake (лучшие книги онлайн TXT) 📗

A book lay open on the small table behind Andrew. He’d apparently eaten his supper while reading by lanternlight.

When he’d dried and put away the last of the dishes, Andrew added wood to the fire, stoked it into a steady blaze, and climbed the ladder up into a loft.

From his cold perspective the voyeur could just make out the furnishings of Andrew’s writing nook—a desk, bookshelves, a typewriter, and little notes (perhaps two dozen of them) affixed to the rafters overhead. A poster of Edgar Allen Poe was also tacked to one of the beams. It fluttered in updrafts from the hearth.

Andrew sat at the desk and then faintly through the glass came the patter of his fingers on the keys.

The master was writing.

Horace grinned, mind racing to process every detail. They would be so important.

This time a year ago he’d just quit the University of Alaska’s MFA creative writing program. The meltdown had occurred during a meeting with his faculty advisor, the thirty-something Professor Byron, just a cocky toddler for the academic world. Horace had decided that his thesis was going to be a collection of short stories, all horror, and when he told this to Byron, the professor laughed out loud.

"What?" Horace said.

"Nothing, it’s just…I mean if you think you’re going to make a name for—"

"I’m sick of writing whiny, my-life-sucks fiction set in suburban kitchens."

"You think that’s what we teach here?"

"I mean, God forbid a story actually have a fucking plot."

"Mr. Boone—"

"You know I tried to read your book, um, what was it called, Fighting the Senses."

Byron stiffened, straightened his glasses.

"Booooooooring. That isn’t what I want to write."

The professor smiled, pure acid, said, "You know who didn’t think it was boring?" and pointed to a cutout of his glowing New York Times review taped prominently to the wall beside a bookshelf. "Now here’s the deal, Mr. Boone. I do not accept your thesis proposal. Come back in a week with a real idea or I’ll bounce your ass. You won’t return for spring semester. Good day." And with that Byron had turned around in his swivel chair and begun typing an email.

So as instructed Horace returned the following week with a new thesis proposal: a comic book. The villain was a pretentious fucking ass named Byron and his superpower was the keen ability to eradicate the joy of writing from starry-eyed students. Horace was the hero, his superpower was quitting, and he stormed out of the office brimming with self-righteous indignation.

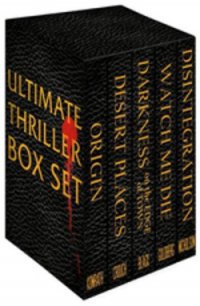

He found a job after Thanksgiving as a bookseller at Murder One Books near the campus, spent days helping customers find the perfect mystery, nights trying to produce his own collection of short horror fiction. After two weeks he’d started twenty stories and abandoned them all. By January he’d quit writing altogether, lost the energy and excitement of creation. Those winter months in Anchorage, he sank through frustration, depression, and settled comfortably into apathy. Fuck writing, reading. He lived for the small pockets of pleasure—a case of Rolling Rock, reality TV, and sleeping. His dream of becoming a writer bowed out with hardly a whimper and he never missed it until one life-changing day.

Shivering, watching the shadows play on Andrew Thomas’s back, he thought of the cold and sunny April afternoon six months prior, when the most infamous suspense novelist in the world had strolled into his Anchorage bookstore and given direction to his life.

Having watched the customer browse the bookshelves for the last forty minutes, I know irrefutably that this is the writer and murderer, Andrew Thomas, regardless of his thick beard and long shaggy hair. It’s the piercing eyes and soft mouth that give him away.

At last he approaches the counter. He looks as I would expect—wary, cold, a man who has seen and done things that most people could not contemplate. My palms sweat, mouth so dry my sandpaper tongue feels leathery and feline.

He sets five hardbacks on the counter. We are alone in this tiny bookstore of new and old mysteries, only marginally larger than a dorm room. It is dim inside the store. The floor and shelves consist of dark knotty wood. There are no windows but this is no shortcoming. Every book is a window.

"Is this all, sir?" I manage.

He nods and my hands tremble as I begin to scan his selections: a used collection of Poe’s short stories, Kafka, three mysteries from one of his contemporaries.

I listen to the rhythm of his breathing—deep comfortable inhalations. I smell the tannin of his leather jacket. His eyes roam over my head to the shelf behind the counter that displays the ten bestsellers of Murder One Books.

"One-oh-three ninety-eight," I say.

He points to the credit card that he’s already placed on the counter. I lift it, almost too urgently, and glance at the name welted upon the plastic: Vincent Carmichael.

I look up from the credit card into his eyes.

He’s staring at me.

I swipe the card, hand it back to him.

Tearing the receipt from the scanner, I lay it down on the counter with a pen and watch him sign Vincent Carmichael in wispy characters that are nothing like his true autograph.

Part of me wants to speak to him, to tell him I’ve read everything he’s ever written. But I hold my tongue, reminding myself that the rumors surrounding this man are legendary—if he knew that I knew he would end me.

So I put his five books into a plastic bag, hand him the receipt, and he walks out the open door into the cold Alaskan afternoon.

He crosses Campus Drive and sits down in bright grass in the shade of a juniper, the tangy gin-scented berries of which I can smell even from inside the store. U of A students recline all around him in the weak sun and shade of saplings scattered through the green—reading, napping, smoking between classes.

And as I stare at Andrew Thomas, a surge of adrenaline fills me and the thrill of inspiration rears its lovely head.

I’ve found my story.

5

I woke Saturday in the Yukon dawn, donned a fleece pullover, and stepped into a pair of cold Vasque Sundowners to save my sockfeet from the frozen floorboards. The Nalgene water bottle on my bedside table was capped with ice. I looked over at the hearth, saw that the fire had reduced itself to a pile of warm fine ash.

I walked out to the woodpile I’d chopped in September. It was stacked seven feet high and stretched for twenty feet between two rampike poplars that had been cooked by lightning last spring. The cold stung. My fingers tingled even through the leather gloves.

I gathered an armload of wood as the sun angled through the spruce branches and thawed the forest floor. The thermometer on the front porch read eight above.

As I reached for the door, something snapped behind me. I froze, turned slowly around, scanned the trees. Twenty yards away an enormous bull moose emerged from the spruce thicket, the branches catching in his giant rack. He walked leisurely behind the woodpile, probably headed for the pond.

Inside I placed a handful of kindling on the metal grate and stacked the logs on end around the twigs in a teepee arrangement. Then I balled up several sheets of the St. Elias Echo and stuffed these beneath the grate. There was a hot coal or two left. These ignited the newspaper which in turn lit the kindling and soon the young flames were tonguing the logs, steaming off the latent moisture, boiling the fragrant resin within.